Drug Effect Analyzer: On-Target vs Off-Target Side Effects

Select a drug to analyze

This tool explains why certain side effects occur and whether they're on-target or off-target

When you take a pill for high blood pressure, diabetes, or cancer, you expect it to fix the problem-not give you a rash, diarrhea, or heart trouble. But side effects happen. And not all of them are accidents. Some are actually the drug working exactly as planned… just in the wrong place. Others? They’re complete surprises-interactions with targets the drug wasn’t supposed to touch at all. Understanding the difference between on-target and off-target drug effects isn’t just for scientists. It explains why some side effects are common and manageable, while others are rare, unpredictable, and dangerous.

What Exactly Is an On-Target Effect?

An on-target effect happens when a drug hits the exact molecule it was designed to target-but that molecule exists in healthy tissues too. Think of it like a key that fits one lock perfectly. The lock is your disease target. But if that same lock exists in your skin, gut, or heart, the key will turn there too. The result? The drug works where you want it to… and where you don’t.Take metformin, a common diabetes drug. It lowers blood sugar by reducing glucose production in the liver. That’s the goal. But it also increases gut motility and alters gut bacteria. That’s why diarrhea is one of its most common side effects. It’s not a flaw-it’s the same mechanism, happening in the intestines instead of the liver. Same key, different lock.

Another example: EGFR inhibitors used in lung cancer. They block a protein that helps tumors grow. But that same protein is vital for skin cell repair. So patients often get severe acne-like rashes. It’s not an allergy. It’s the drug doing its job-just too well-in healthy skin. About 68% of patients on these drugs get this rash, and 22% need their dose lowered because of it.

Statins, used to lower cholesterol, are another classic case. They block HMG-CoA reductase, an enzyme in the liver that makes cholesterol. That’s on-target. But that enzyme also exists in muscle cells. Too much inhibition can lead to muscle pain or, rarely, rhabdomyolysis-a dangerous breakdown of muscle tissue. It’s not random. It’s the same target, in a different tissue.

Off-Target Effects: When the Drug Gets Lost

Off-target effects are the drug’s bad habits. It’s like a key that fits not just one lock, but ten. The drug was meant for one protein, but it accidentally binds to others. These unintended interactions can trigger completely unrelated biological responses.One of the most studied examples is kinase inhibitors-drugs used in cancer. These small molecules are designed to block a single mutated kinase driving tumor growth. But kinases are a huge family of over 500 similar proteins. A typical kinase inhibitor binds to 25-30 of them at therapeutic doses. Imatinib (Gleevec), for example, was made to block BCR-ABL in leukemia. But it also hits c-KIT, which is why it works against gastrointestinal stromal tumors (a bonus). But it also causes fluid retention and swelling because c-KIT is involved in blood vessel regulation.

Even drugs with well-known targets can surprise us. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were originally developed as antimalarials. But during the pandemic, they were tested against COVID-19. Later studies showed they didn’t work by blocking the virus directly. Instead, they changed the pH inside cellular compartments like lysosomes and endosomes-organelles involved in waste processing. That’s off-target. They weren’t designed to do that. But it happened anyway.

And sometimes, off-target effects are worse because they’re invisible until it’s too late. A 2019 case report in the New England Journal of Medicine described a patient on statins who developed severe muscle damage after five years of no issues. No warning signs. No elevated enzymes until it was too late. That’s the scary part of off-target effects-they don’t follow predictable patterns. They’re not dose-dependent in the same way on-target effects are.

Why Do Some Drugs Have More Off-Target Effects Than Others?

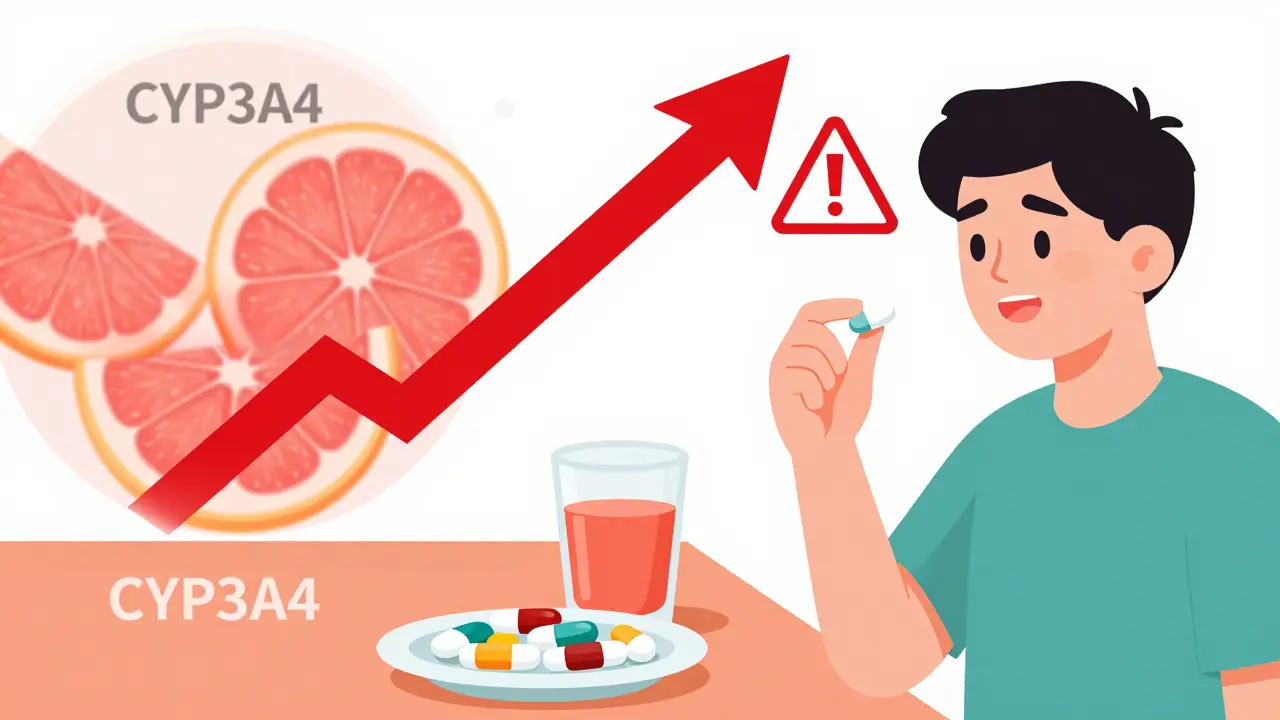

It’s not random. Drug type matters a lot.Small molecule drugs-pills you swallow-are usually the worst offenders. On average, they interact with 6.3 unintended targets at therapeutic doses. Why? They’re small, flexible, and can slip into similar-shaped protein pockets. Kinase inhibitors are the worst, making up 42% of all reported off-target toxicities in the FDA’s database from 2015-2020.

Biologics, like monoclonal antibodies (e.g., trastuzumab/Herceptin), are much more selective. They’re large, complex proteins designed to bind with high precision to one target-like HER2 on breast cancer cells. They average only 1.2 off-target interactions. That’s why their side effect profile is cleaner. But they’re not perfect. Trastuzumab can still cause heart damage. Why? Because HER2 is also present in heart muscle cells. That’s an on-target effect, not off-target. Even highly specific drugs can hurt healthy tissues if the target is shared.

And here’s the twist: sometimes, off-target effects are useful. Thalidomide was pulled from the market in the 1960s because it caused terrible birth defects. But decades later, doctors discovered it helped treat multiple myeloma by modulating the immune system. That immune effect? It was an off-target action. Now, it’s a life-saving drug. Sildenafil (Viagra) was originally developed for angina. Its off-target effect on penile blood vessels turned it into a billion-dollar drug for erectile dysfunction.

How Do Scientists Find These Effects Before People Take the Drug?

Drug companies don’t just guess. They use advanced tools to map out what a drug might hit before it ever reaches a human.One method is chemical proteomics. Scientists attach the drug to a bead, then drop it into a soup of human proteins. Anything that sticks to the bead? That’s a potential off-target. Another technique is KinomeScan, used by Genentech, which tests a drug against hundreds of kinases at once to see which ones it binds to.

More recently, researchers use transcriptomics-looking at which genes turn on or off after drug exposure. In a landmark 2019 study, scientists treated three different cell lines with four different statins. At the gene level, responses were all over the place. But when they looked at pathways-groups of genes working together-they found consistent patterns. The cholesterol pathway was always suppressed (on-target). Immune-related pathways lit up in some cases (off-target). This showed that gene-level noise can hide clear biological signals.

Regulators now require this kind of testing. The European Medicines Agency’s 2021 guidelines say you need at least two different methods to prove you’ve checked for off-target effects. Companies that do this well have a 22% higher chance of getting their drug approved.

What Does This Mean for Patients?

If you’re on medication and get a side effect, ask: Is this the drug working too well… or working in the wrong place?On-target side effects are often predictable, dose-dependent, and manageable. A rash from an EGFR inhibitor? Your doctor might prescribe a topical cream and lower your dose. Diarrhea from metformin? Switch to extended-release or take it with food. These are signs the drug is doing its job-just with collateral damage.

Off-target effects? They’re the wild cards. They’re less predictable, harder to anticipate, and often require stopping the drug entirely. A 2021 survey of over 1,200 doctors found that 82% considered on-target side effects “expected and manageable.” Only 37% felt the same about off-target ones.

That’s why some patients get confused. One Reddit user wrote: “I didn’t realize the diarrhea from my diabetes med was the intended effect working too well in my gut.” That’s on-target. Another patient might get sudden liver damage from a statin with no warning. That’s off-target. One is a known risk. The other is a mystery.

What’s Changing in Drug Development?

The industry is shifting. Ten years ago, most drug discovery focused on finding a single target and designing a molecule to hit it perfectly. That’s still done. But now, many companies are going back to phenotypic screening-testing compounds on whole cells or even animals to see what happens, without assuming the target. Why? Because biology is messy. A drug might have five off-target effects, but if the overall result is good (kills cancer, lowers blood pressure, no major toxicity), it’s worth pursuing.That’s why 60% of first-in-class drugs approved between 1999 and 2013 came from phenotypic screening, not target-based design. Companies like AstraZeneca now combine AI, transcriptomics, and proteomics to predict side effects before human trials. Their approach cut off-target toxicity predictions by 42%.

The future? Drugs won’t just be designed to hit one target. They’ll be designed to hit a target-and avoid others. The Open Targets Platform, used by 87% of top pharma companies, now predicts off-target risks with 87% accuracy using machine learning. The FDA’s 2023 guidance on tissue-agnostic cancer drugs pushes this even further: you must test how a drug affects every tissue where the target is expressed.

By 2030, experts predict that drugs with fully mapped on-target and off-target profiles will make up 78% of the global pharmaceutical market. Precision medicine isn’t just about matching drugs to genes. It’s about matching drugs to people-by understanding exactly how they’ll react, both on and off target.

Final Thoughts: It’s Not Just About the Drug

Side effects aren’t failures. They’re signals. On-target effects tell you the drug is working. Off-target effects tell you biology is more complex than we thought.There’s no perfect drug. But the best drugs are the ones where scientists understood the trade-offs. Where they knew the key fit more than one lock-and chose to live with the consequences, or redesigned the key to avoid them.

For patients, the lesson is simple: if you get a side effect, don’t assume it’s an accident. Ask your doctor: Is this the drug working too hard in the right place? Or is it doing something it wasn’t meant to do? That distinction changes everything-from how you manage symptoms to whether you keep taking the medicine.

What’s the difference between on-target and off-target side effects?

On-target side effects happen when a drug hits its intended target but that target exists in healthy tissues-like skin rash from cancer drugs that block skin repair proteins. Off-target effects occur when the drug accidentally binds to unrelated proteins, causing unexpected reactions like liver damage or heart rhythm changes. One is the same mechanism in the wrong place; the other is a completely different biological interaction.

Are off-target effects always dangerous?

No. While many off-target effects cause harm, some turn out to be beneficial. Thalidomide was withdrawn for causing birth defects, but later found to treat multiple myeloma by modulating the immune system-an off-target effect. Sildenafil was developed for heart disease but became Viagra after its off-target effect on penile blood vessels was noticed. These cases show off-target effects aren’t always bad-they’re just unintended.

Why do some people get side effects and others don’t?

Genetics, age, liver/kidney function, and other medications all play a role. But with off-target effects, it’s often about subtle differences in protein structures. One person might have a slightly different version of a kinase that the drug accidentally binds to-making them sensitive. Another person’s version doesn’t bind, so they’re unaffected. That’s why off-target effects are hard to predict and often appear only in a small subset of patients.

Can drug companies prevent off-target effects?

They can reduce them, but not eliminate them. Modern drug discovery uses chemical proteomics, AI models, and high-throughput screening to identify off-target interactions early. Companies like Genentech and Novartis use tools like KinomeScan to test drugs against hundreds of proteins before human trials. But biology is complex-some interactions only show up in humans, not in cells or animals. So while risk is lowered, it’s never zero.

Are biologics safer than small-molecule drugs?

Generally, yes. Monoclonal antibodies and other biologics are larger and more specific, averaging only 1.2 off-target interactions compared to 6.3 for small molecules. But they’re not risk-free. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) can damage the heart because HER2 is present there too-that’s an on-target effect. So safety depends on the target, not just the drug type.

The dichotomy between on-target and off-target pharmacodynamics is fundamentally a matter of polypharmacological promiscuity versus target specificity. When a small molecule engages with kinome-wide off-targets-often due to conserved ATP-binding pockets-it’s not a flaw, it’s an emergent property of molecular topology. The 6.3 average off-targets per small molecule isn’t noise-it’s statistical inevitability given the structural homology across the human proteome. We need to stop pathologizing polypharmacology and start engineering for it.

Let me be clear: this isn’t just about drug design-it’s about humility in science. For decades, we treated biology like a machine with isolated parts, and we thought if we could just hit the right switch, everything would work perfectly. But life isn’t a circuit board. It’s a symphony. When metformin alters gut motility, it’s not malfunctioning-it’s resonating with another note in the same chord. When statins cause muscle pain, it’s not a bug-it’s the harmonic overtone of a system we barely understand. We don’t need more precision drugs. We need more wisdom in how we interpret their effects. The side effect isn’t the enemy. The arrogance that assumes we control the outcome is.

Oh my god, I just realized my chronic diarrhea from metformin isn’t me being ‘sensitive’-it’s the drug doing its job in my intestines?! I’ve been blaming my diet for years. This explains why my cousin on the same med doesn’t have it-her gut flora must be different. I feel seen. And also, kinda violated. Like my body was a side project for a liver experiment. But also… kind of brilliant? Like the drug’s got a secret second life. Can we start calling these ‘collateral benefits’ instead of ‘side effects’? Less scary, more poetic.

lol u guys are overcomplicating this. statins cause muscle pain because they lower coq10. thats it. no fancy proteomics needed. also thalidomide caused birth defects because it was given to pregnant women. duh. and viagra was a happy accident. big whoop. this article is just a long winded way of saying ‘drugs have side effects’. i could’ve written this in 10 mins. also typo: ‘kinase inhibitors’ is misspelled in paragraph 3. lol.

Of course the pharma giants want you to believe off-target effects are ‘complex’-it lets them dodge liability. They knew about the kinase promiscuity for years. They just didn’t care until the lawsuits started piling up. And don’t get me started on how they market ‘on-target’ side effects as ‘expected’ to scare patients into compliance. That rash from EGFR inhibitors? It’s not ‘manageable’-it’s disfiguring. And they charge $15,000 a month for it. This isn’t science. It’s profit-driven exploitation dressed up as precision medicine.

off target = bad on target = bad both = profit

statins = muscle pain

metformin = diarrhea

egfr = rash

all predictable

all ignored

all billed

end of story

Hey everyone-just wanted to say this thread is actually really important. I’ve been a nurse for 18 years, and I’ve seen patients panic because they think side effects mean the drug is ‘failing’ or they’re ‘broken.’ But this breakdown? It’s the clearest explanation I’ve seen. On-target = same mechanism, wrong location. Off-target = the drug wandered into the wrong room. That’s it. And honestly? We need to teach this in high school biology. Patients deserve to understand their meds-not just take them. If you’re on a drug and get a side effect, ask: ‘Is this the key turning in the wrong lock-or is it picking a lock it wasn’t meant to touch?’ That question changes everything.

Oh wow. So the reason I got a rash from my cancer drug is because my skin cells have the same protein as the tumor? How poetic. Like my body was just… collaborating with the cancer. I’m flattered. Meanwhile, my oncologist just handed me a tube of hydrocortisone and said ‘it’s normal.’ Normal? My face looks like I lost a fight with a cactus. And now you’re telling me this was *intentional*? Congratulations, science-you turned my epidermis into a collateral damage zone. At least sildenafil turned its off-target into a billion-dollar boner. My rash? Still just a rash. And still itchy.