Every year, hundreds of thousands of people end up in hospitals not because their condition got worse, but because the medicine meant to help them made things worse. These are called adverse drug reactions-unexpected, harmful responses to medications that aren’t due to overdose or misuse. In New Zealand, the UK, and the US, up to 7% of all hospital admissions are linked to these reactions. Many of them are preventable. And the key to stopping them isn’t more careful prescribing-it’s knowing what’s in your genes.

How Your Genes Control How Medicines Work

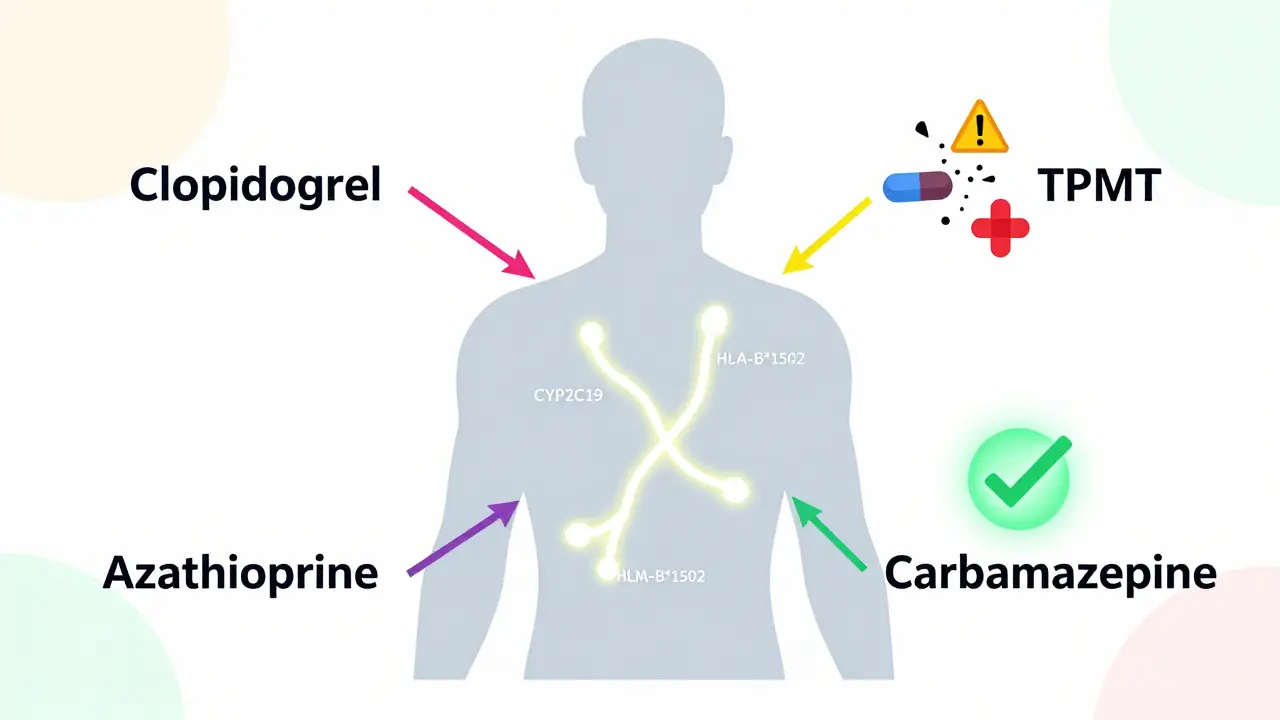

Your body doesn’t process every drug the same way. Two people taking the same pill at the same dose can have completely different outcomes. One feels better. The other ends up in the ER with a severe rash, liver damage, or dangerously low blood cell counts. Why? Because of small differences in their DNA. Genes like CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and TPMT act like traffic controllers for drugs. They tell your liver how fast to break down medications. If you have a variant that slows this process, the drug builds up in your system. Too much? Toxicity. Too little? The drug doesn’t work. For example, about 2-5% of people of Asian descent carry the HLA-B*1502 gene variant. If they take carbamazepine for epilepsy or nerve pain, they have a 100 times higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome-a life-threatening skin reaction. Testing for this variant before prescribing cuts that risk by 95%.The PREPARE Study: Proof That Testing Saves Lives

For years, doctors suspected that genetic testing could reduce these reactions. But proof was missing. That changed in 2023 with the PREPARE study, a three-year trial across seven European countries involving nearly 7,000 patients. Researchers gave participants a single genetic test before they started any new medication. The test looked at 12 genes linked to how the body handles over 100 common drugs-including antidepressants, blood thinners, painkillers, and cancer treatments. The results were clear: patients who had their genes checked before taking medication had a 30% lower rate of serious adverse reactions compared to those who didn’t. That’s not a small number. It means for every 100 people tested, about 30 avoided a hospital visit, a dangerous side effect, or worse. What made this study different was that it wasn’t done in a lab or a specialty clinic. It was done in real hospitals, with real doctors, using real electronic health records. The test results popped up as alerts when a doctor tried to prescribe a drug that could be risky for that patient’s genes.Which Genes Matter Most?

Not every gene matters for every drug. But a handful are well-documented and used in clinical practice today. Here are the top five gene-drug pairs with the strongest evidence:- CYP2C19 and clopidogrel (Plavix): Used after heart attacks. About 2-5% of people are poor metabolizers-they can’t activate the drug. These patients have a much higher risk of another heart attack. Testing prevents that.

- TPMT and azathioprine: Used for autoimmune diseases and leukemia. People with low TPMT activity can develop life-threatening drops in white blood cells. Testing reduces this risk by 78%.

- SLCO1B1 and simvastatin (Zocor): A cholesterol drug. Certain variants increase the risk of muscle damage. Testing helps doctors choose a safer dose or alternative.

- DPYD and fluorouracil (5-FU): A common chemotherapy drug. People with DPYD mutations can die from toxicity. Testing is now standard before treatment in many countries.

- HLA-B*1502 and carbamazepine: As mentioned, this variant is a red flag for severe skin reactions in Asian populations.

These five alone cover more than 20% of commonly prescribed medications. And the list keeps growing. In 2024, the FDA updated its list of pharmacogenetic associations to include 329 gene-drug pairs-up from 287 just two years earlier.

How Testing Works in Practice

Getting tested isn’t complicated. A simple cheek swab or blood draw is all it takes. Labs use genotyping chips that scan for known variants with 99.9% accuracy. Results come back in 24 to 72 hours. In hospitals that have integrated the system, the report appears directly in the electronic health record. When a doctor selects a drug, a pop-up says: “Patient has CYP2C19 poor metabolizer status. Avoid clopidogrel. Consider alternative.” This isn’t science fiction. The University of Florida Health system has been doing this since 2012. Since then, they’ve seen a 75% drop in ADR-related emergency visits among tested patients. The initial cost was $1.2 million for infrastructure, but they recovered that investment in 18 months-just from avoiding hospital stays and emergency care.Why Isn’t Everyone Doing This Yet?

The science is solid. The data is clear. So why isn’t every doctor ordering this test? One reason: cost. A full panel test runs between $200 and $500. That’s not cheap. But when you consider that a single ADR can cost over $20,000 in hospital bills, it’s a bargain. In fact, 78% of economic studies show pharmacogenetic testing saves money over time. Another barrier: doctors don’t feel confident interpreting results. A 2022 survey found only 37% of physicians felt comfortable using pharmacogenetic data. Many don’t know what “intermediate metabolizer” means, or how to adjust doses for someone who’s both a slow and fast metabolizer for different drugs. Training helps. Programs like the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) offer free, updated guidelines for 34 gene-drug pairs. But adoption lags-especially in primary care, where only 18% of clinics use testing, compared to 65% in oncology. There’s also the issue of diversity. Most genetic data comes from people of European descent. Variants common in African, Indigenous, or Pacific Islander populations are still poorly understood. That means a test might miss a risk-or give a false warning. The NIH and others are working to fix this, with new studies adding over 100 previously unknown gene-drug links from underrepresented groups.

What’s Next?

The future of pharmacogenetics isn’t just about single genes. Researchers are now building polygenic risk scores-models that combine dozens of small genetic effects to predict how someone will respond to a drug. Early results show these scores are 40-60% more accurate than single-gene tests. Costs are also falling. Companies are developing point-of-care PCR tests that could bring the price of a full panel down to $50-$100 by 2026. Some hospitals are even storing DNA samples from newborns or during routine blood tests, so the data is already there when needed. The European Commission has committed €150 million to roll out preemptive testing across member states by 2027. In the U.S., Medicare now covers testing for clopidogrel and thiopurines. More insurers are following.Should You Get Tested?

If you’re taking-or might take-multiple medications, especially for chronic conditions like depression, heart disease, or cancer, pharmacogenetic testing could be one of the most important health decisions you make. It doesn’t change your genes. It just helps your doctor choose the right drug at the right dose the first time. Most patients-85%-say they’d be willing to get tested if their doctor recommended it. The biggest concern? Privacy. But the data used in these tests doesn’t reveal your risk for cancer, Alzheimer’s, or other diseases. It only looks at how your body handles drugs. That’s it. The truth is, we’ve been guessing how medicines affect people for over a century. Pharmacogenetic testing ends that guesswork. It’s not magic. It’s science. And it’s ready.Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance?

In the U.S., Medicare and some private insurers cover testing for specific high-risk drug-gene pairs like CYP2C19 before clopidogrel and TPMT before azathioprine. Coverage varies by plan and state. In Europe, countries like the Netherlands and Germany have national programs that include testing in routine care. Always check with your insurer or healthcare provider before ordering a test.

How long does it take to get results?

In most hospital settings with integrated labs, results are available in 24 to 72 hours. Some commercial labs take up to two weeks, especially if the test is ordered privately. Turnaround time is getting faster as technology improves, with some clinics now offering same-day results using point-of-care devices.

Can pharmacogenetic testing predict if I’ll get addicted to painkillers?

No. Pharmacogenetic testing looks at how your body metabolizes drugs-not how your brain responds to them. It can tell you if you’ll break down opioids quickly or slowly, which affects dosage and side effects. But it cannot predict addiction risk, mental health responses, or cravings. Those involve complex brain chemistry and environmental factors beyond current genetic testing.

Do I need to be retested if I get a new drug later?

No. Your genes don’t change. Once you’ve had a full pharmacogenetic panel done, the results apply for life. You won’t need to be tested again for the same genes, even if you start new medications years later. The challenge is making sure your doctor has access to those results when prescribing.

What if my test shows I’m a slow metabolizer?

It doesn’t mean you can’t take the drug-it means you need a lower dose or an alternative. For example, if you’re a slow metabolizer of codeine, your body can’t convert it to morphine effectively, so you won’t get pain relief. Your doctor might switch you to a different painkiller. If you’re a slow metabolizer of warfarin, you’ll need a much smaller dose to avoid bleeding. The goal isn’t to avoid meds-it’s to use them safely.