The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change how drugs get approved in the U.S.-it rewrote the rules of the entire pharmaceutical market. Before 1984, generic drugs were rare. Fewer than 10 were approved each year. Today, nine out of every 10 prescriptions filled are for generics. That shift didn’t happen by accident. It was built on a single law: the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.

Why the Hatch-Waxman Act Was Needed

In the early 1980s, generic drug makers faced a legal wall. The Supreme Court had ruled in Roche v. Bolar that testing a patented drug before its patent expired-even just to gather data for FDA approval-was patent infringement. That meant generic companies couldn’t start preparing to launch until the patent expired. For a drug with a 20-year patent, that could mean waiting over a decade after the drug hit the market just to get started. Brand-name companies, meanwhile, were frustrated. The FDA approval process could take years, eating into their patent clock. By the time a drug reached consumers, it might have only five or six years of market exclusivity left. That didn’t give them enough time to recoup their R&D costs. The Hatch-Waxman Act solved both problems at once. It created a legal compromise: generic companies could begin testing drugs before patents expired, and innovator companies could get extra patent time to make up for the years lost during FDA review. It was a deal brokered by Congress, not forced by either side. And it worked.How Generic Drugs Got Approved Faster

The heart of the Act is the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Before Hatch-Waxman, every new drug-whether brand or generic-had to go through full clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness. That cost hundreds of millions of dollars and took years. The ANDA changed that. Generic manufacturers no longer needed to repeat those expensive studies. All they had to prove was that their version was bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That means it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. The FDA estimates this cuts development costs by about 75%. To make this work, the FDA created the Orange Book, a public list of all approved drugs and their patents. Generic companies use this to identify which patents they need to challenge before launching. It’s the roadmap for generic entry.The Patent Game: Extensions and Challenges

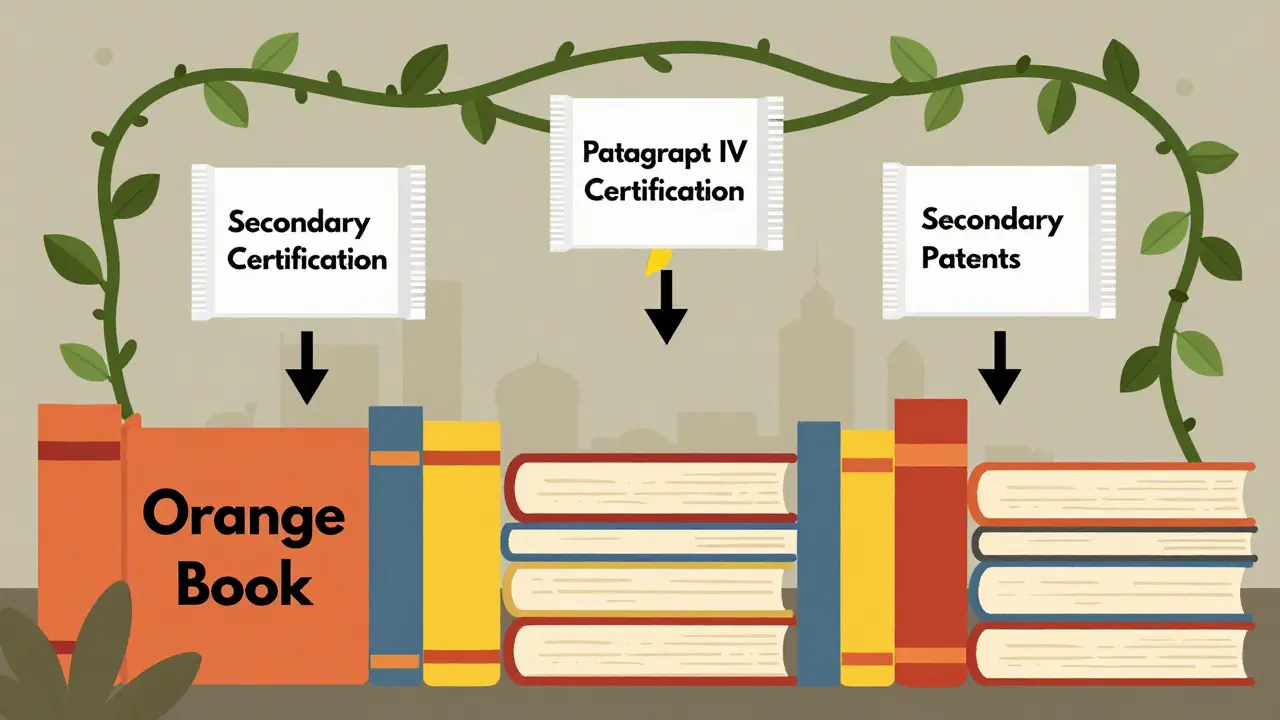

One of the most powerful tools in the Act is patent term restoration. If a drug’s patent clock was slowed down by FDA review, the innovator company could apply for up to five years of extra protection-but no more than 14 years total after FDA approval. In practice, the average extension granted was just 2.6 years. That sounds modest, but for a blockbuster drug, even a few extra months of exclusivity can mean billions in revenue. On the flip side, the Act created the Paragraph IV certification. This lets a generic company say, “We believe this patent is invalid or we won’t be infringing it.” When they file that, the brand-name company has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA is legally required to delay approval for 30 months-unless the court rules sooner. This system was meant to encourage competition. But it also created a loophole. The first generic company to file a Paragraph IV challenge gets 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. That’s a huge incentive. In the 1990s, companies would literally camp outside FDA offices to be the first to submit. The FDA later changed the rules to allow shared exclusivity if multiple companies filed on the same day-but the race still exists.

What Went Wrong: Patent Thickets and Pay-for-Delay

The Act was designed to balance innovation and access. But over time, both sides found ways to game the system. Brand-name companies began filing dozens of patents on minor changes-new coatings, dosages, or delivery methods. These are called secondary patents. In 1984, the average drug had 3.5 patents listed in the Orange Book. By 2016, that number jumped to 2.7 per drug. Today, it’s common to see 14 or more patents on a single drug. This creates a patent thicket-a legal maze that delays generics for years. One tactic, called product hopping, involves slightly changing a drug-like switching from a pill to a tablet-and then pushing doctors to prescribe the new version. Once the original patent expires, the new version gets its own patent clock. Generics can’t enter until that new patent runs out. Even worse is pay-for-delay. In these deals, brand-name companies pay generic manufacturers to delay launching their cheaper version. Between 2005 and 2012, about 10% of all generic challenges ended in these settlements. The FTC called them anti-competitive. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled they could be illegal-but they still happen.Who Wins and Who Loses

The numbers speak for themselves. Since 1991, the Hatch-Waxman Act has saved U.S. consumers over $1.18 trillion in drug costs. In 2022 alone, generics saved $313 billion. Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions but only 18% of total spending. But the savings aren’t evenly distributed. The top 10 generic manufacturers now control 62% of the market. Smaller companies struggle with the cost and complexity. Preparing an ANDA can take 24 to 36 months and cost $15 million to $30 million in legal fees. That’s why many small firms get bought out before they even launch. Meanwhile, innovator companies have extended their effective market exclusivity by an average of 2.8 years since 1984-not because of the law, but because of how they’ve used it. The average drug now gets 13.2 years of market protection before generics arrive, up from 10.4 years before the Act.

What’s Changing Now

The system is under pressure. In 2022, Congress passed the CREATES Act, which stops brand companies from refusing to sell samples of their drugs to generic makers. Without those samples, generics can’t even test their product. In 2023, the House passed the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which would ban pay-for-delay deals outright. The FDA has also started cracking down on improper patent listings in the Orange Book. New guidance aims to prevent companies from listing patents that don’t actually cover the drug’s use. Under GDUFA IV, the FDA plans to cut ANDA review times from 10 months to 8 months by 2025. That’s a big deal. Every month saved means generics hit the market faster. But there’s a risk. Too much pressure on patents could hurt innovation. Japan saw a 34% drop in new drug approvals after it reformed its generic system in 2018. The U.S. still leads the world in new drug development-partly because Hatch-Waxman gives companies the financial incentive to take the risk.The Bottom Line

The Hatch-Waxman Act isn’t perfect. It’s been stretched, twisted, and exploited. But without it, we wouldn’t have the generic drug system we have today. It’s the reason you can fill a prescription for $4 instead of $400. It’s why millions of Americans can afford their medications. The real question isn’t whether the Act works-it’s whether we can fix its flaws without breaking what still works. The solution isn’t to scrap it. It’s to tighten the loopholes, enforce the rules, and keep the balance alive.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act, officially called the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, is a U.S. law that created a legal pathway for generic drugs to enter the market while giving brand-name drug companies extra patent time to make up for delays during FDA approval. It established the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) process and the patent term restoration system.

How do generic drugs get approved under Hatch-Waxman?

Generic companies file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA. Instead of repeating full clinical trials, they prove their drug is bioequivalent to the brand-name version already approved. They must also address any patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, either by waiting for them to expire or by challenging them with a Paragraph IV certification.

What is the Orange Book?

The Orange Book, formally called the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, is a public list maintained by the FDA. It includes all approved drugs, their active ingredients, manufacturers, and any patents associated with them. Generic companies use it to identify which patents they need to challenge before launching.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement made by a generic drug applicant claiming that a patent listed in the Orange Book is either invalid or won’t be infringed by their product. Filing this triggers a 45-day window for the brand-name company to sue. If they do, FDA approval is automatically delayed for 30 months unless the court rules sooner.

Why do some generic drugs take years to launch after a patent expires?

Even after a patent expires, generic entry can be delayed by secondary patents, litigation, or pay-for-delay agreements. Brand companies often file dozens of patents on minor changes, creating a legal barrier. Courts can take years to resolve disputes, and some generic companies accept payments to delay entry-both of which slow down competition.

Has the Hatch-Waxman Act saved money?

Yes. Between 1991 and 2011, the Act saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.18 trillion. In 2022 alone, generic drugs saved $313 billion. Generics make up 90% of prescriptions but only 18% of total drug spending, making them one of the biggest drivers of cost savings in U.S. healthcare.

Can’t believe how much this law quietly changed everyday life. I used to pay $200 for my blood pressure med. Now it’s $4 at Walmart. No one talks about this, but it’s one of the biggest wins for regular people in modern policy.

So let me get this straight - we created a system where drug companies get paid billions to not compete, and then we call it ‘innovation’? 😏

Patent thickets? More like patent spam. Product hopping? That’s not innovation, that’s legal whack-a-mole. And pay-for-delay? That’s just bribery with a law degree.

It’s wild how we reward monopoly behavior and call it capitalism. 🤔

Generic drugs are the ultimate proof that competition works - but the system’s rigged to avoid it. We’re not fixing a broken system… we’re just arguing over who gets to keep the keys to the vault.

I read somewhere that the first generic company to file a Paragraph IV gets 180 days exclusivity… which sounds like a reward for being first… but also incentivizes gaming the system… I don’t know if that’s a bug or a feature… maybe both?

Also the Orange Book thing… I didn’t realize it was public… that’s kinda cool… like a drug patent map…

My grandma takes 7 meds. All generics. She wouldn’t be alive today without this law. Honestly? I don’t care if Big Pharma complains. If they want to make money, make better drugs - don’t just tweak the color of the pill and call it a new product.

It’s fascinating how the law was designed to balance two sides, but both sides found ways to exploit it. The 180-day exclusivity window was meant to encourage competition, but it ended up creating a new kind of monopoly. And the patent extensions? They were supposed to be a small compensation… but now they’re the main event.

I wonder if we need a new kind of review process - something that looks at whether a patent is truly innovative or just a legal loophole.

India has its own version of this - but we don’t have the same patent games. We make cheap generics and send them to Africa and Latin America. The US system is smart… but it’s also too rich to be fair.

Big Pharma thinks they’re geniuses. But really? They just learned how to turn law into a money printer. 😅

90% of prescriptions are generics… and yet we still treat them like second-class meds. 🙄

My pharmacist once told me a brand-name version was "more reliable" - I asked for proof. She didn’t have any. The FDA says they’re identical. So why do we still believe the brand name is better? It’s marketing. Pure and simple.

While the Hatch-Waxman Act has undeniably facilitated access to affordable therapeutics, the unintended consequences - particularly the proliferation of secondary patents and the institutionalization of pay-for-delay arrangements - have significantly undermined its original intent. A recalibration of the Paragraph IV framework, coupled with enhanced transparency in Orange Book listings, is imperative to restore the equilibrium between innovation and accessibility.

wait so if a company files a patent on a blue pill instead of a red one… and then switches to blue… and then generics cant make the red one anymore… thats legal???

i feel like i missed a memo on how this is even a thing

It’s easy to hate Big Pharma, but without the incentive of patent protection, would we ever have gotten new cancer drugs in the first place? The system’s flawed, but it’s still the best we’ve got. Maybe the answer isn’t to tear it down - just to fix the loopholes.

The philosophical tension here is profound: the state must incentivize innovation while simultaneously ensuring equitable access. The Hatch-Waxman Act attempted a utilitarian compromise, yet the emergent behavior of market actors has revealed a structural asymmetry - the cost of litigation and regulatory compliance disproportionately burdens smaller entities, thereby concentrating market power. A systemic recalibration is not merely desirable - it is ethically imperative.

They gave us $1.18 trillion in savings… and then spent $10 billion lobbying to keep the loopholes open. Classic. 😏

Next up: the FDA starts charging $500 just to look at a generic application. Can’t have too much competition, right?