When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, it doesn’t just open the door for one generic competitor-it triggers a chain reaction. The first generic to hit the market gets a 180-day window to dominate sales and pricing. But after that, things get messy. Competitors flood in, prices crash, and the market becomes a battlefield of cost-cutting, legal maneuvering, and supply chain chaos. This isn’t just about cheaper pills. It’s about how the system works, who wins, who loses, and why shortages keep happening even when there are dozens of manufacturers claiming to make the same drug.

The 180-Day Window: First Mover Advantage

The first generic company to challenge a brand’s patent and win gets something rare in pharma: a legal monopoly. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, that company can sell its version without competition for six months. During this time, it captures 70-80% of the market. Prices stay high-often 70-90% of the original brand price-because there’s no alternative yet. This isn’t greed; it’s survival. Patent litigation costs $5-10 million on average. The first generic needs that window to recoup its investment. Take Crestor (rosuvastatin). When its patent expired in 2016, the first generic entered and held nearly 80% of sales. Within months, prices dropped from $320 a month to under $100. But it wasn’t until eight other companies joined that the price hit $10. That’s the pattern: the first entrant makes money. The rest fight for scraps.Why the Second and Third Entrants Change Everything

The real price crash doesn’t happen with the second generic. It happens with the third. According to the FDA’s 2022 data, when one generic is on the market, prices are at 83% of the brand. With two, they drop to 66%. With three, they plunge to 49%. That 17-point drop between two and three competitors is the steepest in the entire cycle. Why? Because now buyers have real choice. Pharmacies, PBMs, and hospitals start playing manufacturers against each other. This is where authorized generics come in. These aren’t knockoffs-they’re the brand company’s own version, sold under a different label. Merck did this with Januvia in 2019. On the exact day the first generic launched, Merck rolled out its own authorized version. Within six months, it captured 32% of the market. The first generic’s share dropped from 80% to 50%. The brand didn’t lose revenue-it just stopped pretending it was gone.How Later Entrants Play the Game

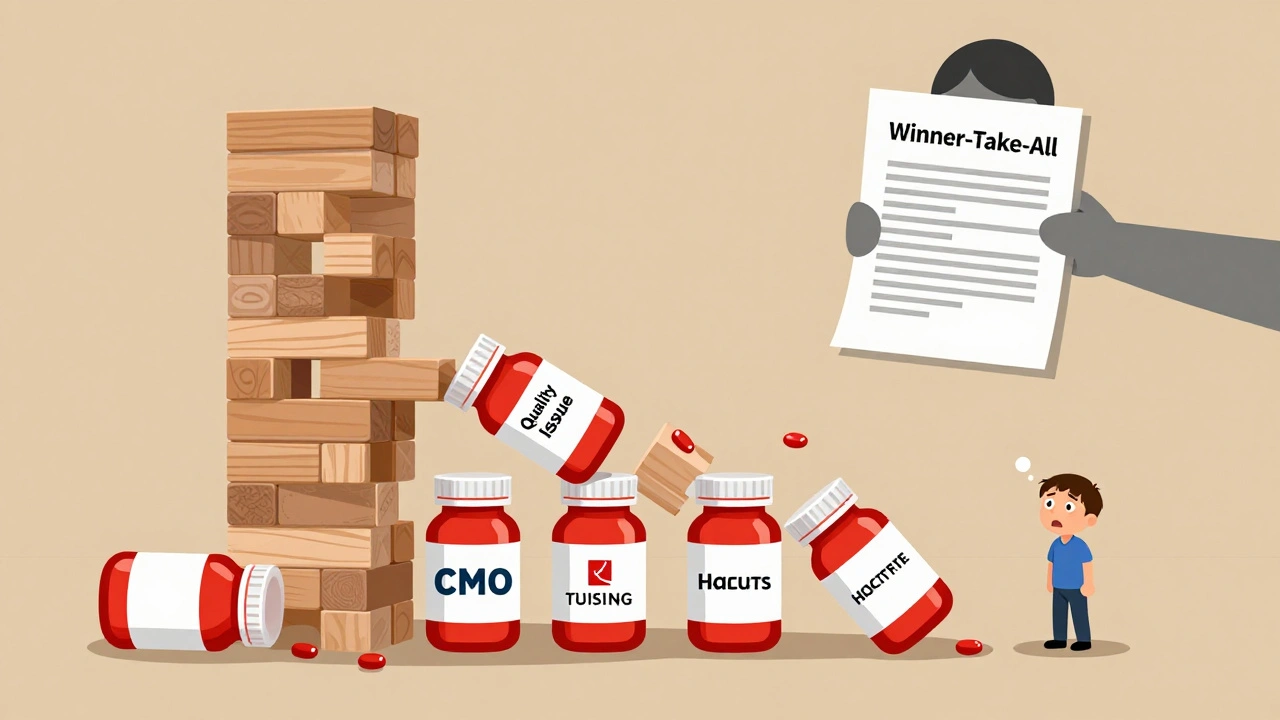

Companies entering after the first don’t have to reprove bioequivalence. They can piggyback on the first generic’s work. That cuts development costs by 30-40%. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. The real hurdles are outside the lab. First, they need samples. Before the CREATES Act of 2020, brand companies could refuse to sell samples to generic makers, stalling entry for over a year. Now, it takes under five months. Still, brand companies fight back. Between 2018 and 2022, they filed over 1,200 citizen petitions targeting drugs with even one generic already approved. Each petition delays the next entrant by an average of 8.3 months. Then there’s distribution. The first generic gets preferred placement with major pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). Later entrants face a gauntlet: 48 different state licensing rules, GPOs demanding 30-40% discounts, and PBMs that use “winner-take-all” contracts. If you’re not the top bidder, you get zero formulary access-even if your drug is FDA-approved. In 2023, 68% of generic contracts were structured this way. The first generic to sign a deal often locks in 80-90% of the business.

Manufacturing: The Hidden Bottleneck

Most generic drugs aren’t made by the companies selling them. They’re outsourced to contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs). The first generic often owns its own facility. But subsequent entrants? They rent space. That’s cheaper, but riskier. In 2022, the FDA found that 78% of second-and-later generic manufacturers relied on CMOs, compared to just 45% of first entrants. That’s why shortages spike after multiple generics enter. Sixty-two percent of all generic shortages involve drugs with three or more manufacturers. One CMO has a quality issue? Five brands go out of stock overnight. And when prices are already at 17% of the brand, there’s no profit margin to fix it. This has led to consolidation. In 2018, there were 142 companies holding generic drug approvals. By 2022, that number dropped to 97. The market is shrinking because too many players entered too fast, prices collapsed, and the ones without scale got crushed.Therapeutic Categories Don’t Play by the Same Rules

Not all generics are created equal. Cardiovascular drugs like atorvastatin or metoprolol hit 12-15% of brand prices with five competitors. But oncology drugs? They hover at 35-40%. Why? Because they’re harder to make. They need sterile environments, special handling, and tighter controls. Fewer companies can make them. So competition stays low. CNS drugs-like antidepressants or antipsychotics-stabilize around 20-25%. These drugs have more complex absorption profiles. Bioequivalence testing takes longer. That slows down entry. And when they do enter, the market doesn’t collapse as fast. Biosimilars are a whole different ballgame. They’re not chemical copies-they’re biological. Development costs run $100-250 million. So even with four competitors, prices only drop to 50-55% of the brand. That’s why biosimilars don’t trigger the same price crash. They’re more like premium generics.

10 Comments

Write a comment